|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Studio! | ||||

At home in the control room; simple, modest, and almost totally homemade. Image © 2013 Chris Bell |

||||

2012 marked the completion of my new recording studio at the Tritschler Precision Engineering Headquarters in Enon, OH, and this page has been assembled in response to numerous requests for more information about my scratch-built console, microphones, and other stuff I used to make The Doctor Is IN!. I've been recording almost as long as I've been playing guitar, and building recording equipment nearly as long as I've been tinkering with amplifiers; the two have truly worked in parallel from the very beginning. I'm proud to report that this is the first studio I've had the freedom to design without being constrained by apartments, landlords, or living with my parents. One of my objectives in the design of the studio was to have the absolute least amount of gear possible. In an age where imported, mass-produced recording gear and instruments are so incredibly cheap and it is so tempting to want to equip oneself with as many tools as possible, I wanted to get back to an age where the gear was largely handmade, cost a serious fortune (which it still does for the real-deal stuff), and was built to last a lifetime. To that end, I've resorted to designing and building most of the studio gear myself. One aspect of the studio that may surprise those familiar with how this stuff works is that my entire operation is high-impedance, unbalanced, and totally transformerless, inspired by the hi-fi approach the Sax brothers pioneered with their Mastering Lab in Hollywood in the 1960's. Another thing is that I don't use equalization. If I had to characterize my overall recording aesthetic, I'd say that I simply prefer raw, natural, unaffected sound. Which isn't to say that I won't put a little compression on a lead vocal or tape-delay the echo chamber, go for a slightly dirty bass sound; hell, even flange a whole mix if the feeling is right. But as for the audio shenanigans that became very en vogue a few decades ago and still haunt popular music; no thanks. Finally, I'd like to emphasize that although I often come across as an audio elitist and indeed run in some extremely pretentious audiophile circles, I firmly believe that whatever sounds good is good and this is just my particular path. |

||||

| The Control Room | ||||

| My control room consists of a 12-channel console with tube microphone preamps and discrete FET line and summing amplifiers; eight-track, two-track, and mono analog tape machines; Electro-Voice monitor speakers with custom dividing networks and amplification; and a homemade two-channel optical compressor. That's it. Oh, and a tube amplifier driving my live echo chamber. I have a two-channel digital recorder lying around somewhere for when I have to prepare CD and download masters. It's not a large room, but has been very carefully proportioned and treated with wide-band absorption to have very uniform reverberation characteristics. The walls are not splayed; flutter echoes are controlled with strategically-placed absorption panels consisting of cheap fiberglass insulation in wooden frames, covered with decorative fabric. I have to credit Everest & Pohlmann's Master Handbook of Acoustics, Fifth Edition for a superb "working man's" approach to room design and treatment; and a very special thank you to Billy Horton in Austin, Texas for leading the way. The large absorbers surrounding the monitor speakers in the above photo serve five purposes; flutter echo control, pattern and edge diffraction control of the horns and bass-reflex woofer cabinets, wide-band control of overall reverberation decay time, absorption of early reflections from the surfaces behind the speakers, and LF modal control, which is helped by the airspace between the panels and the corners of the room. Not bad for a few bucks' worth of materials from Lowe's and JoAnn Fabric. As with hi-fi listening rooms, experimentation with speaker and absorber placement is crucial. | ||||

| The Console | ||||

At the heart of my control room is the console I started building in the summer of 1996, before my senior year of high school. At that time, I had just gotten my most prized posession; a perfect-condition Ampex AG440B-8 1" eight-track tape machine, "permanently loaned" to me by an attorney in Lorain, Ohio, who is now a judge. Why did I endeavor to build a mixing console as a teenager? Enthralled by old photographs of bespectacled recording engineers sitting at these gorgeous battleship-grey behemoths that cost as much as a mansion and made some of the most incredible recordings of all time, I just couldn't get excited by some little thing you could buy in a music store. It got even worse when I looked at the schematic of one and saw more integrated circuits than you could shake a stick at. So I decided to build a mixer with tube microphone preamps and the rest discrete-transistor; eighteen channels just in case I ever got a 16-track 3M M79 tape deck like my hero, Henry Hirsch. I bought a bunch of surplus rack panels at Fair Radio Sales in Lima, Ohio and got to work. Well, the console turned out to be the never-ending project of a lifetime, until I finally finished it in November 2009. I had actually machined the panels and gotten all the mike preamps working by the time I graduated high school and had mostly designed the rest by 2001, even built the case; but it seemed like every few years I'd get a better idea for the audio circuitry and redesign it. At some point I decided enough was enough and that I needed to get the damned thing working before it entered a third decade of incompletion. I ended up sticking with eight tracks and scaled the console down to twelve channels, making a somewhat-reasonable package that fit on a chopped Steelcase desk. |

||||

One proud papa! The night I got everything finished except the monitor/talkback section, as evidenced by the blank panel over the large VU meters. Image ©2009 Jason Bailey |

||||

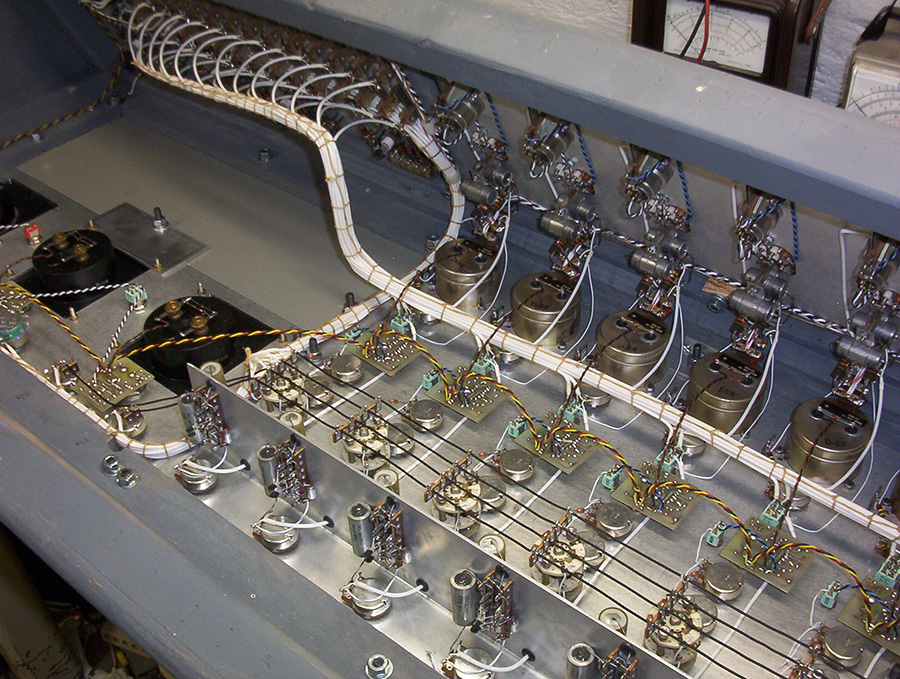

| I used the best materials I could get in this console, almost all from surplus; places like Fair Radio, Midwest Surplus Electronics in Fairborn, and Mendelson's in Dayton. Thank heavens I started stockpiling all this crap in the 90's before it started to really dry up. Gudeman XHF paper-in-oil caps in the preamps; hermetically-sealed Gudeman polystyrene and wax/paper Sprague caps in the line and summing amps; Allen-Bradley carbon-comp and mil-spec Dale RN-type metal film resistors; silver/Teflon aircraft-grade wire; and silver-contact mil-spec ceramic wafer switches. The whole signal path, even the solid-state stuff, is point-to-point wired on terminal strips and turret boards; the only circuit boards in the console are used for the peak indicator and meter driver circuitry, and I etched those after-hours in the EE department lab at Wright State. My mother, Elizabeth Tritschler, harnessed the wiring going to the patch-panel with waxed string, military-style. Lambda regulated power supplies are used throughout. Before I forget, I also need to thank Chris Ivan, Roger and Kimberly Hughes, Alan Zonker, Nathan Haskell, and John Haines. Without them, I never would have made it out of the gate. | ||||

A 'peak' under the hood! My mother laced all the wiring together with waxed string like old military gear. An extra-special thanks goes to supreme machinist, mold-maker, and motorcycle racing champion Alan Zonker, who helped me machine the big meter holes and hand-bent the line amplifier brackets; a true life-saver. Photo © 2009 Joe Tritschler |

||||

| As far as functionality goes, this mixer is about as simple as it gets. Each channel has a microphone gain control, mike/line switch, two mono echo sends, left-center-right and mute switches, and a rotary fader. The master panel has a talkback circuit, headphone amplifier, and facilities for monitoring various sources in either mono or stereo. It's very quiet and reliable. | ||||

My father, Tony Tritschler, manning the controls in the short-lived original configuration of the studio control room. Every time I ask him to come over and do a live-to-two-track mix while I'm out in the studio jamming, he gives me a line of crap about not knowing what he's doing. Yeah, right...who taught me all this stuff? Photo © 2012 Terry Greenlee |

||||

| Would I design the console differently if I was starting from scratch today? Absolutely, both ergonomically and electronically, although I may have a very hard time topping its sound. But even if I build another one, and I most certainly will when the large second studio I'm planning comes to fruition, this console means so many things to me and has traversed so many different phases of my life, I'll never discard it. | ||||

| Microphones | ||||

| I have six microphones, which is one more than Sam Phillips had available at the Memphis Recording Service; five handbuilt tube mikes and an EV dynamic for the bass drum. Okay, eight if you count the two early-80's Crown PZM-30GPB's in my echo chamber. Two of the tube mikes use Microtech Gefell UM-70 head assemblies, which feature PVC-skinned M7 capsules like a Neumann U-47 or M-49; and in fact the Gefell M7 capsules are still made today exactly the same way they were when Georg Neumann set up the factory in the 1940's. My microphones, however, feature cathode-follower amplifiers which then drive the input grids of my console preamps directly without any transformers in the signal path. This is in contrast to traditional microphone designs which have a voltage amplifier followed by a stepdown transformer, usually with another transformer at the input of the preamp. The transformerless cathode-follower approach has lower distortion, wider bandwidth, and strikingly higher fidelity, which isn't necessarily what many "vintage" microphone enthusiasts want. In a small studio with less than 50-foot cable runs, this setup is still dead quiet, despite being unbalanced. The venerable AKG C-60, Sony C37A, and Altec 21B mikes are traditional examples of cathode-follower mikes that drove a pretty substantial cable without a transformer, although an output transformer was then located in the power supply. | ||||

Custom transformerless cathode-follower Microtech Gefell UM-70 mike; Hammond A-102 organ and Baldwin Acrosonic piano in the background. Image ©2013 Kristin Kay |

||||

| My three other tube microphones use AKG "CMS" System capsules, as found on C-451 and similar mikes, and I have CK-1 cardioid, CK-2 omni, and CK-5 blast-filtered vocal cardioid heads available. These are also transformerless cathode-follower mikes, partially inspired by David Royer's infamous article in Glass Audio in 1996, The Country Boy's Capacitor Microphone. The Royer article specified Primo CM-23B capsules in the mikes, which I built to the letter with help from my grandfather as a teenager, and they never sounded all that good; absolutely no top end at all. Later I noticed that the photograph in the article was of a mike with an AKG CK-1 capsule! Some ten years later I designed a new miniature microphone body and asked Casey Simmons, who made all my guitars, to machine three of them for me out of brass, and even designed Teflon capsule connectors for them. | ||||

| Tape Machines | ||||

I record to analog tape and always have because it's the sound and workflow I greatly prefer. I've also worked in digital studios and made records for other people on Pro Tools and all that stuff, and it's fine; I certainly appreciate other people's preferences and have heard some mighty good-sounding digital recordings. There may not be any tape recorder manufacturers left, but there are still at least two companies making high-quality recording tape and a number of people manufacturing and refurbishing things like tape heads and precision transport components, so I intend to keep working this way for a long time. I've had the same two-track analog tape machine since I was a third-grade kid; a Crown SX-722 deck my father picked up in the early-80's from the WOSU radio station in Columbus, Ohio for 100 bucks. No, that wasn't a typo; my dad really gave me an industrial tape recorder in a giant grey rack when I was eight years old. I made all kinds of hilarious overdubbed home recordings right off the bat and later cut my tape machine maintenance/setup/modification teeth on that thing; figured out how to modify it for 15 inches per second and got the equalization and bias right the same summer I started my console. John Haines, who was Crown's service manager from 1965 to 1977 and started a business in Goshen, Indiana supporting old Crown decks some 30 years ago, has been selling me parts and keeping my machines tip-top from the very beginning; he supplied me with new drive motor bearings and NOS Nortronics heads for this deck and pulled together all the parts needed to build two essentially-new portable SX-722's, which I keep for live recording, backup decks, and for the real tape flanging on the tune "Snakebite!" on The Doctor Is IN! |

||||

Triple Crown SX-722 tape recorders! The oscillator, power amplifier, and transformer setup on the chair was for the flanging effect on the tune "Snakebite!" on The Doctor Is IN! My mother controlled the frequency of the second capstan motor while I mixed. I hope she didn't think she was out of the woods on stuff like this just 'cause I'm a grown man. Image ©2012 Joe Tritschler |

||||

The electronics in my main recorder are very heavily modified and have been rebuilt a few times, and there's no question that these decks have their own mechanical peculiarities that I've learned to intuit and work with over the last 25 years, but I still prefer that old thing over anything else I've had here, including Ampex AG440B's, Otari decks, and even the Studer A-80 I used at SoundSpace in Yellow Springs when I worked there. Maybe I'm just sentimental. On the other hand, the Crown Pro-700 transport, which came out around 1967, is so bone-simple it doesn't even have relays, let alone transport logic or tension control, and yet for some reason I feel the large belt-driven flywheel makes for a solidity of sound that's just different and special, like a Thorens TD-124 turntable. The mono deck in the portable case sitting on top of my main deck in the control room photo is one I built for my Master's Thesis in 2003. It's a Crown Pro-700 transport and a gutted tube Crown RP-3 electronics unit (relax, it was already trashed), rebuilt with a special tube recording circuit I came up with called the sigma-transadmittance amplifier. I thought I was very clever, electronically summing the bias and audio signals into a low-distortion transresistance amplifier driving the record head with no traps or resonant circuits, but it turns out Tandberg did something along those lines - albeit with solid-state circuitry and probably a lot more stages - in the 1970's. Oh well. I've made mono rockabilly records on it and mainly use it for slap echo and pre-delaying my echo chamber, and there's something about the sound that makes me want to build stereo and multitrack decks with that circuit; maybe someday when I have some free time (!). |

||||

Photo taken from my 2003 Master's Thesis! I got the machine fully working at the stroke of midnight on my 24th birthday. Image ©2003 Fred Garber, Department of Electrical Engineering, Wright State University |

||||

| Besides the console, the other cornerstone of my studio is an early-80's MCI JH110C-8 1" eight-track tape machine. Having long since given the Ampex eight-track back to the gentleman in Lorain, I needed one for the studio and found it on the Nashville craigslist. Call it fate, call it a cosmic alignment of epic proportions, call it a sheer coincidence, but the owner happened to be singer/songwriter B.J. O'Malley from Youngstown. Small world. | ||||

The MCI eight-track the day I drove her home from Nashville. Thank you, BJ. Image ©2012 Joe Tritschler |

||||

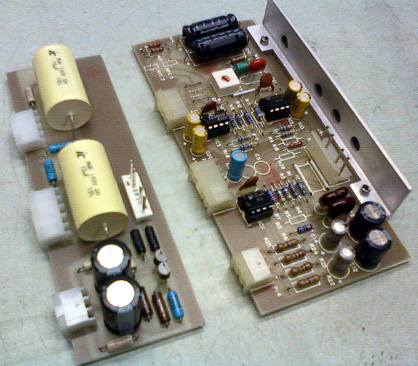

| There's really nothing special about the MCI machine; it uses 5534-type op-amps for Pete's sake, but it's really been a good-sounding, very-reliable machine once I cleaned all the IC socket and Molex pins. The Ampex 440 eight track was a classic, highly-desirable, very hip machine, no doubt about it, but then again, when it comes to punching in quickly and silently and shuttling tape with precision and grace, I have to say the MCI just kills it. I did fabricate new I/O cards so the machine would have the same unbalanced 100-kΩ input impedance as the old Ampex (and which my console was designed to drive), and elected to use a discrete-transistor design with film capacitors and mil-spec resistors. I intend to design discrete record and playback cards too at some point. | ||||

New (left) and original (right) I/O cards for the MCI JH110C-8. Which would you rather have; three 5534 op-amps, or two Class-A NPN Darlington transistors? I was able to eliminate the differential balanced output stage completely and capacitively couple the playback cards right to the console. Big improvement. Image ©2012 Joe Tritschler |

||||

| Compressor | ||||

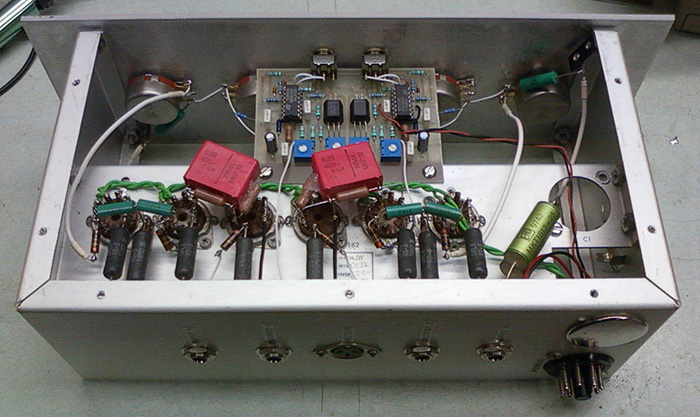

| As I mentioned previously, I don't use equalization and in fact don't have any in the studio; but I do have a two-channel compressor I'll use when I want a little special something on a vocal or lead guitar track, and just a little bit on the final mix. It's the two-tone grey thing with the big meters in the same rack as my two-track Crown machine in the control room photo. I actually began the design work on my compressor in 2001 as a senior in college, but abandoned it and resumed the work in 2010. Billy Horton has my original prototype in Austin, Texas. It's an optical design like a Teletronix LA-2A, but uses LED-driven Vactrol optoisolators and a special control circuit. The make-up amplifier is tube and has an elaborate regulated power supply built around a Tektronix 160. I had a little "trouble" with the consistency of the Vactrol units; the trouble being that the time constants varied horribly, at least with the type I used. Out of 20 units I purchased, three had release times in the range I needed, and with sufficient matching for a stereo pair. But the result is something I really like. Ratio is set to a very gentle 4:1 and, like most optos, has a fairly slow attack and release, placing it squarely in the compressor category and definitely not a peak limiter. | ||||

Inside the compressor. The make-up amplifier is all-tube. ©2012 Joe Tritschler |

||||

| Monitoring | ||||

| My monitor speakers are essentially Electro-Voice theater speakers with custom electronics driving them. The horns are HP-940 with DH-1A drivers and the woofers are twin DL15X in the TL606DX enclosure. I got these from the Charlotte Coliseum when they tore it down and allegedly the voices of Frank Sinatra and Mother Teresa have been through them! I didn't want to use the E-V XEQ-3 crossover/equalizer unit that comes with this system and elected to design a new one. Equalization for the constant-directivity horns is now passive and buffered, with a shelving instead of peaking characteristic, and I'm using E-V's "stepdown" tuning on the woofers with one of the ports closed off. The crossover frequency is set to 630 Hz, first-order, and the horns are driven with 12-watt triode tube amps, woofers with big ol' solid-state. I don't advise the use of first-order crossovers in sound reinforcement, but in this-sized room, you'd spontaneously combust from the volume level before anything blew up, trust me. It's an extremely accurate, dynamic system. | ||||

| The Studio | ||||

| Enough nerdy equipment talk; let's talk about the actual room in which the music is recorded! My studio is not large; only about 3,000 cubic feet, but again, it's been carefully proportioned and treated and works well. I have only the essential instruments; a hodgepodge 50's/60's Slingerland drum kit with Ludwig snare, a Hammond A-102 organ with 31H "tallboy" Leslie (147 amplifier and drivers), and a humble but good-sounding Baldwin Acrosonic piano. It's all I need. | ||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| All studio photos ©2013 Kristin Kay | ||||